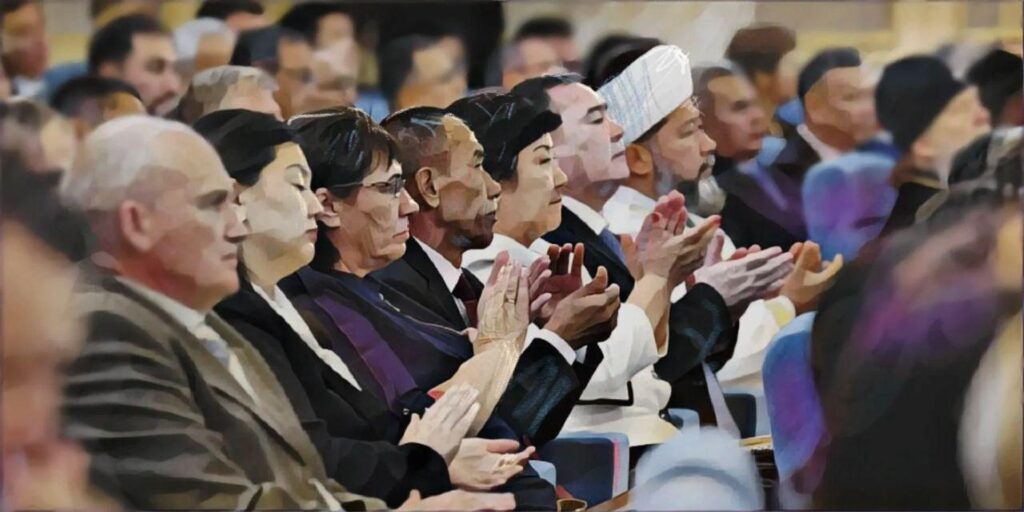

On the Eve of Valentine’s Day: Customs of Love and Marriage in Central Asia

On the eve of Valentine’s Day, Central Asia is once again debating whether to celebrate the holiday or regard it as a symbol of foreign influence. Yet the region has its own rich and diverse customs related to love, matchmaking, and marriage. Accusations of Alien Influence and “Corruption” Valentine’s Day, like Halloween, spread to the former Soviet republics after the collapse of the USSR. In the first decades, young people embraced the new holidays. In recent years, however, critics have increasingly argued that commemorating a Catholic saint in a format centered on romantic love contradicts the traditions of the region’s peoples. For example, in Kazakhstan last year, deputies of the Mazhilis, the lower house of parliament, sharply criticized Valentine’s Day. Some deputies argued that it corrupts young people, promotes “free love,” and even carries “homosexual overtones.” It is worth noting that Kazakhstan recently adopted legislation prohibiting so-called “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations.” The Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Kazakhstan has also stated that Valentine’s Day promotes alien values and encourages promiscuity. Gratitude for Raising a Daughter Many matchmaking and marriage customs remain common across Central Asia, particularly the significant role of the bride’s and groom’s parents in ceremonies and celebrations. While traditions have evolved, many are still practiced in modern engagements and weddings. The well-known custom of paying bride price, kalym, has been preserved, though it has undergone significant change. Today, kalym varies depending on the wealth of the families. It may include apartments or cars, or it may amount to several hundred dollars. Importantly, kalym is now generally regarded as financial support for the young family and, as a rule, remains at the disposal of the bride and groom. Historically, in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, kalym was paid in livestock, and wedding celebrations could last more than a month. One of the main Kazakh wedding rituals is the groom’s visit to the bride’s village or, in modern practice, her home. Before his first visit, the groom sends gifts to the bride’s family, known as Ilu, an expression of gratitude for raising their daughter. In some regions of Kazakhstan, this ritual is called ana suty (“mother’s milk payment”). In the past, it included horses, camels, sheep, and riding equipment for the bride’s father. Today, it may consist of any valuable gift, and jewelry is often presented to the women in the bride’s family. The bride traditionally gives the groom a scarf as a symbol of her purity. Festivities then begin, with singing and dancing. Kazakh traditions often involve two weddings: one at the bride’s home and one at the groom’s. The bride’s farewell from her family home remains especially significant, reflecting her relatives’ wishes for her future life. Today, this ceremony is often held in a restaurant. The bride does not wear a white wedding dress at the farewell celebration but appears in an elegant outfit and a traditional headdress known as a saukele. During the farewell, the groom and his friends are subjected to playful pranks, for which they must pay with gifts or money. One of the oldest traditions is the performance of the zhar-zhar song contest. A group of women sings about the sorrow of parting and the uncertainties of married life, while a group of men responds with reassurance. Historians trace this tradition to pre-Islamic times, when marriages were sealed with community approval and communal singing. Today, the main wedding ceremony begins with the official registration of marriage at a government office. According to custom, the groom’s relatives were once not permitted to see the bride before the wedding. When she entered her husband’s home, the betashar (face-revealing) ceremony was performed, symbolizing her introduction to her new family and married life. Traditionally, the mother-in-law removed the bride’s shawl and cut it into pieces, symbolizing wishes for many children. Today, betashar is largely a ceremonial tradition, as families are typically well acquainted beforehand. Religious Kazakh couples may also hold a marriage ceremony in a mosque on the same day. Modern weddings have incorporated European-style elements, including decorated car processions and visits to scenic locations. Kyrgyz wedding customs closely resemble Kazakh traditions, with distinctive features of their own. For example, kulak choyu is a popular custom in which children playfully pull the groom’s ears until they receive money. Another ritual, chachyla, involves showering the newlyweds with sweets as the bride enters the groom’s home, symbolizing wishes for prosperity and happiness. No Wedding Without Pilaf In Uzbekistan, similar to European custom, the bride holds a kiz osh before the wedding, a women-only celebration comparable to a bachelorette party. The bride presents gifts to her friends. A similar men-only celebration is held at the groom’s home. The number of guests may reflect the family’s social standing. This is followed by nikah-tui, the religious wedding ceremony conducted by an imam. The couple vows mutual respect and allegiance to each other and their families. The bride wears a traditional dress and veil, believed to protect her from the evil eye. The imam must obtain the bride’s consent, often communicated through a female representative. Relatives then bid farewell to the bride before the traditional wedding feast begins. The main dish is pilaf, typically prepared by men. The celebration includes music, dancing, and abundant food. In Tajikistan, matchmaking also plays a central role. During this process, the wedding date and the size of the mahr and kalina (dowry) are agreed upon. Neighbors and relatives attend the engagement ceremony, where rituals such as fotiha (a prayer marking the beginning of an undertaking) and nonshikanon (breaking of flatbread) are performed. The most respected elder breaks the bread and offers prayers for the couple’s future. The bride’s family distributes safedi, white fabric symbolizing purity and chastity. In Turkmenistan, wedding customs are carefully preserved while incorporating modern elements. Scarves play a significant role. At the gelin toy (wedding at the bride’s home), women carry gifts and sweets wrapped in scarves. Upon departure, they receive bundles of equal value. In men’s competitions, winning a scarf is considered a prestigious prize. The wedding procession, once composed of camels and horses and now of cars, is decorated with colorful scarves that are later distributed to guests and drivers. One of the most complex elements of a Turkmen wedding is the ritual transition from girlhood to womanhood. The bride’s braids are tucked behind her back; a small scarf is removed and replaced with a larger one. Occasionally, a child attempts to seize the old scarf. The mother-in-law returns it to the bride for a small ransom. The bride keeps the scarf until her own child marries, when it is passed on to the next generation. Thus, despite debates over foreign holidays devoted to love, Central Asia continues to preserve its distinctive traditions of matchmaking and marriage.

Pannier and Hillard’s Spotlight on Central Asia: New Episode – B5+1, Sanctions, and a New Constitution – Out Now

As Managing Editor of The Times of Central Asia, I’m delighted that, in partnership with the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, from October 19, we are the home of the Spotlight on Central Asia podcast. Chaired by seasoned broadcasters Bruce Pannier of RFE/RL’s long-running Majlis podcast and Michael Hillard of The Red Line, each fortnightly instalment will take you on a deep dive into the latest news, developments, security issues, and social trends across an increasingly pivotal region. This week, the team will be covering the B5+1 summit in Bishkek, the prospect of new EU sanctions targeting Kyrgyzstan, fresh complications around Rosatom's nuclear plans in Uzbekistan, shake-ups inside Uzbekistan's internal security services, and some genuinely surprising new drug-use statistics coming out of Tajikistan. We'll also look at the latest shootout on the Tajikistan–Afghanistan border. And then, for our main story, we will be diving into Kazakhstan's newly released draft constitution and what it signals about where the political system is heading next. On the show this week: - Yevgeny Zhovtis (Human Rights Activist) - Aiman Umarova (Kazakh Lawyer) Hosted by Bruce Pannier and Michael Hilliard

Uzbekistan Approves Feasibility Study for Trans-Afghan Railway

President Shavkat Mirziyoyev has approved an intergovernmental agreement on the joint development of a feasibility study for the construction of the Trans-Afghan railway, which will link Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. According to the presidential resolution, the agreement between Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Transport, Afghanistan’s Ministry of Public Works, and Pakistan’s Ministry of Railways provides for the preparation of technical and economic documentation for a new railway line from Naibabad to Kharlachi. The document formalizes cooperation on the next stage of the long-discussed regional transport corridor. Under the resolution, Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been instructed to notify the Afghan and Pakistani sides that all necessary domestic procedures required for the agreement’s entry into force have been completed. The Trans-Afghan railway project was first proposed by Tashkent in December 2018 as a strategic initiative to provide Central Asia with direct access to Pakistani seaports. The original concept envisaged extending Afghanistan’s rail network from Mazar-i-Sharif through Kabul and Logar province before crossing into Pakistan. An earlier proposed route was expected to pass through Nangarhar province and the Torkham border crossing into Peshawar. In July 2023, however, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, and Afghanistan agreed on a revised alignment. The updated route will run from Termez to Naibabad, then through Maidan Shahr and Logar to Kharlachi, excluding the previously discussed Torkham crossing. Once connected to Pakistan’s railway network, cargo will be able to reach the Pakistani ports of Karachi, Gwadar, and Qasim. The railway is expected to stretch approximately 647 kilometers. According to recent statements by Uzbek officials, the estimated construction cost is $6.9 billion, although earlier projections ranged from $4.6 billion to $7 billion. The project is regarded by the participating countries as a key component of efforts to strengthen regional connectivity and expand trade routes between Central and South Asia.

Opinion: Afghanistan and Central Asia – Security Without Illusions

Over the past year, Afghanistan has become neither markedly more stable nor dramatically more dangerous, despite how it is often portrayed in public discourse. There has been neither the collapse that many feared, nor the breakthrough that some had hoped for. Instead, a relatively unchanged but fragile status quo has persisted, one that Central Asian countries confront daily. For the C5 countries, Afghanistan is increasingly less a topic of speculative discussion and more a persistent factor in their immediate reality. It is no longer just an object of foreign policy, but a constant variable impacting security, trade, humanitarian issues, and regional stability. As such, many of last year’s forecasts have become outdated, based as they were on assumptions of dramatic change, whereas the reality has proven far more inertial. Illusion #1: Afghanistan Can Be Ignored The belief that Afghanistan can be temporarily “put on the back burner” is rooted in the assumption that a lack of public dialogue or political statements equates to a lack of interaction. But the actions of Central Asian states show that ignoring Afghanistan is not a viable option, even when countries intentionally avoid politicizing relations. Turkmenistan offers a clear example. Ashgabat has maintained stable trade, economic, and infrastructure ties with Afghanistan for years, all with minimal foreign policy rhetoric. Energy supplies, cross-border trade, and logistical cooperation have continued despite political and financial constraints, and regardless of international debates over the legitimacy of the Afghan authorities. This quiet pragmatism stands in contrast to both isolationist strategies and symbolic or ideological engagement. Turkmenistan may avoid making public declarations about its relationship with Afghanistan, but it nonetheless maintains robust cooperation. This calculated calmness reduces risks without signaling disengagement. Importantly, this approach does not eliminate structural asymmetries or deeper vulnerabilities. But it dispels the illusion that distancing reduces risk. On the contrary, sustained economic and logistical ties foster predictability, without which attempts to “ignore” a neighboring country become a form of strategic blindness. In this sense, Turkmenistan’s experience affirms a broader regional truth: Afghanistan cannot be removed from Central Asia’s geopolitical equation by simply looking away. It must be engaged pragmatically or dealt with later, in potentially more destabilizing forms. Illusion #2: Security Is Achieved Through Isolation Closely related to the first is the illusion that security can be ensured by building walls. Security in Afghanistan, and in the broader Afghan-Pakistani zone, is often seen as an external issue, something that can be kept out by sealing borders or minimizing engagement. Yet in practice, security is determined less by geography and more by the nature of involvement. This is reflected in the recent decision by Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to participate in U.S. President Donald Trump's “Board of Peace” initiative. While the initiative focuses on resolving crises outside Central Asia, both countries have framed their participation as essential to their own national and regional security interests. As Abdulaziz Kamilov, advisor to the President of Uzbekistan, explained, Tashkent’s involvement stems from three factors: its own security needs, its foreign policy principles, and the recognition that the Middle East remains a region of vital interest to Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan’s past experience supports this logic. During periods of conflict in the Middle East, Uzbeks and other Central Asians were drawn into international terrorist networks, posing significant security threats upon their return. The interconnection between Afghanistan, the Middle East, and Central Asia is clear. According to the Uzbek authorities, terrorist organizations entered Afghanistan from elsewhere, primarily conflict zones in the Middle East. Given this framing, Uzbek officials have argued that Afghanistan often functions as a transit environment rather than the source of extremist threats. Kazakhstan's recent move to join the Abraham Accords, a diplomatic framework aimed at reducing tensions in the Middle East, is similarly revealing. Though at first glance the decision may appear to lie outside Central Asia’s immediate interests, it reflects an understanding that regional instability is contagious. In an era when radical ideologies and transnational threats ignore borders, participation in conflict-mitigation mechanisms, even those based outside the region, is no longer symbolic. It is a form of pre-emptive security. Security today is less about hard boundaries and more about proactive engagement. In this light, efforts to isolate are not only ineffective but they may also prove counterproductive, depriving states of influence in regions where risk is incubated. Illusion #3: Recognition Equals Control Another persistent illusion is that formal recognition of Afghanistan’s government confers control or influence, while its absence renders engagement difficult or illegitimate. But diplomatic practice paints a different picture. As of February 2026, multiple foreign diplomatic missions are active in Afghanistan, including embassies from all Central Asian countries. Other nations with diplomatic representation include Russia, China, India, Iran, Pakistan, Turkey, the Gulf states, Japan, and the European Union. Beyond Kabul, multiple provinces also host consulates. Mazar-i-Sharif hosts several regional consulates, including those of Russia and Turkmenistan, along with other neighboring states. Iran, Turkey, and Turkmenistan are present in Herat, and Pakistan maintains a consulate in Nangarhar. This broad diplomatic presence is not merely symbolic. These missions underscore a critical reality: formal recognition has not been a prerequisite for functional engagement. Instead, countries have pursued de facto diplomacy, addressing issues such as security, trade, logistics, humanitarian aid, and border management. This blurs the once-binary view of “recognition vs. isolation.” In effect, the continued presence of Central Asian missions in Afghanistan suggests that pragmatic engagement now outweighs normative debates. Influence and risk management come through sustained presence and open channels, not formal status. From Illusions to Realism The common flaw in many approaches to Afghanistan is the tendency to treat it as a project, whether political, economic, or integrational. This perspective breeds unrealistic expectations and inevitable disappointment. Afghanistan is not a project for Central Asia. It is a permanent geopolitical factor. It cannot be “switched off” from regional dynamics. The task for Central Asia is not to solve Afghanistan but to coexist with it, based on pragmatism, not illusion. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the publication, its affiliates, or any other organizations mentioned.

A Eurasian Imprint on Judo’s Paris Grand Slam

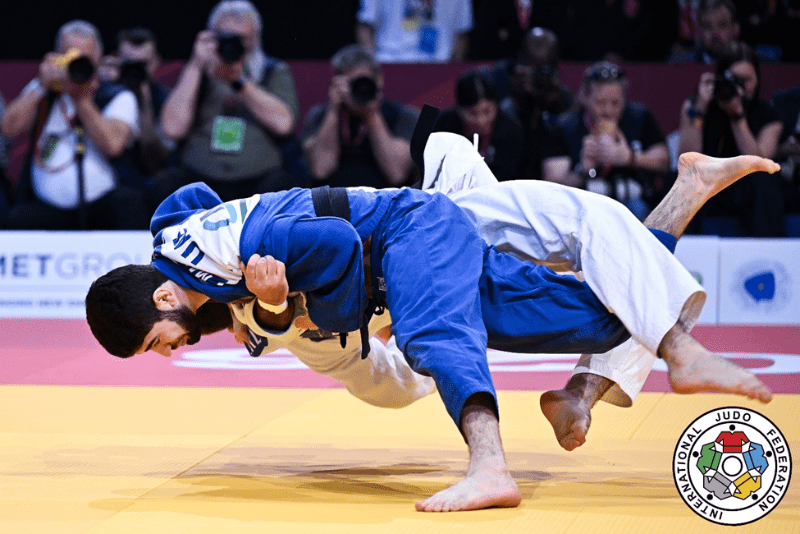

The Paris Judo Grand Slam took place on February 7–8 at a sold-out Accor Arena, drawing more than 20,000 spectators to one of the sport’s most prestigious annual events.

Held under the auspices of the International Judo Federation (IJF) as a flagship stop on the IJF World Tour, the competition carried significant world-ranking points early in the qualification cycle for the Los Angeles 2028 Olympic Games. Nearly 500 athletes from 78 countries participated.

While Japan and France dominated the medal table at the Paris Judo Grand Slam, the tournament also underscored a quieter but enduring force in international judo: the sustained competitive influence of Central Asia and the South Caucasus.

Japan topped the medal table with gold medals from Takeshi Takeoka (–66 kg), Yuhei Oino (–81 kg), Goki Tajima (–90 kg), and Dota Arai (–100 kg). France secured three home victories through Shirine Boukli (–48 kg), Sarah-Léonie Cysique (–57 kg), and Romane Dicko (+78 kg).

The remaining titles reflected the tournament’s global reach. Balabay Aghayev delivered gold for Azerbaijan at –60 kg, Distria Krasniqi won –52 kg for Kosovo, Rafaela Silva captured –63 kg for Brazil, Makhmadbek Makhmadbekov claimed the –73 kg title representing the United Arab Emirates, and Szofi Özbas secured the –70 kg title for Hungary, according to official IJF results.

While Azerbaijan is geographically part of the South Caucasus, its Turkic cultural ties, Soviet-era sporting systems, and shared wrestling traditions closely align with Central Asia’s judo landscape. Aghayev’s gold for Azerbaijan, alongside Makhmadbekov’s –73 kg victory, highlighted transnational athlete pathways rooted in a common Eurasian combat sports tradition.

Makhmadbekov—an ethnically Tajik judoka born in Russia—has represented the United Arab Emirates in international competition since 2024, reflecting the increasingly transnational nature of elite judo careers.

[caption id="attachment_43589" align="aligncenter" width="800"] 73 kg Final: Makhmadbek Makhmadbekov (United Arab Emirates) vs. Manuel Lombardo (Italy); image: Tamara Kulumbegashvili[/caption]

Kazakhstan’s national judo team reinforced that regional presence by concluding the Paris Grand Slam with three bronze medals, one of its strongest results in the tournament’s history. Aman Bakhytzhan reached the podium in the –60 kg division, while Abylaikhan Zhubanazar (–81 kg) and Nurlykhan Sharkhan (–100 kg) added further medals on the second day.

[caption id="attachment_43590" align="aligncenter" width="796"]

73 kg Final: Makhmadbek Makhmadbekov (United Arab Emirates) vs. Manuel Lombardo (Italy); image: Tamara Kulumbegashvili[/caption]

Kazakhstan’s national judo team reinforced that regional presence by concluding the Paris Grand Slam with three bronze medals, one of its strongest results in the tournament’s history. Aman Bakhytzhan reached the podium in the –60 kg division, while Abylaikhan Zhubanazar (–81 kg) and Nurlykhan Sharkhan (–100 kg) added further medals on the second day.

[caption id="attachment_43590" align="aligncenter" width="796"] 60 kg Final: Balabay Aghayev (Azerbaijan) vs. Dilshot Khalmatov (Uzbekistan); image: Tamara Kulumbegashvili [/caption]

Martial arts occupy a distinctive place across Central Asia and Azerbaijan, where indigenous wrestling traditions long predate modern Olympic disciplines. Styles such as kurash in Uzbekistan, kazakh kuresi in Kazakhstan, and gushtingiri in Azerbaijan, alongside their more traditional forms such as gulesh and zorkhana-influenced pekhlivan wrestling, emphasize balance, explosive throws, and physical control. These attributes remain clearly visible in contemporary judo.

These traditions continue to be showcased at events such as the World Nomad Games and regional festivals across Central Asia and the Caspian region. They were further refined during the Soviet era, which institutionalized sports and established the region as a major development base for elite combat athletes.

Since gaining their independence, Central Asian countries, as well as Azerbaijan, have continued to produce high-level judoka, with shared coaching lineages and training systems consistently feeding the top tiers of international competition. Olympic champions such as Yeldos Smetov from Kazakhstan, Diyora Keldiyorova from Uzbekistan, and Elnur Mammadli from Azerbaijan, alongside long-time world-level contenders including Abiba Abuzhakynova, point to the region’s sustained presence at the sport’s highest level—a pattern previously noted by The Times of Central Asia during its coverage of the Paris 2024 Olympic cycle.

That influence extends beyond the competitors themselves. Following the conclusion of the opening-day contests in Paris, Timur Kemell, a member of the official International Judo Federation (IJF) ceremony delegation of Kazakh origin, took part in presenting the medals. Kemell has been active in regional and international judo governance and development, participating in events organized under the auspices of the IJF.

[caption id="attachment_43588" align="aligncenter" width="812"]

60 kg Final: Balabay Aghayev (Azerbaijan) vs. Dilshot Khalmatov (Uzbekistan); image: Tamara Kulumbegashvili [/caption]

Martial arts occupy a distinctive place across Central Asia and Azerbaijan, where indigenous wrestling traditions long predate modern Olympic disciplines. Styles such as kurash in Uzbekistan, kazakh kuresi in Kazakhstan, and gushtingiri in Azerbaijan, alongside their more traditional forms such as gulesh and zorkhana-influenced pekhlivan wrestling, emphasize balance, explosive throws, and physical control. These attributes remain clearly visible in contemporary judo.

These traditions continue to be showcased at events such as the World Nomad Games and regional festivals across Central Asia and the Caspian region. They were further refined during the Soviet era, which institutionalized sports and established the region as a major development base for elite combat athletes.

Since gaining their independence, Central Asian countries, as well as Azerbaijan, have continued to produce high-level judoka, with shared coaching lineages and training systems consistently feeding the top tiers of international competition. Olympic champions such as Yeldos Smetov from Kazakhstan, Diyora Keldiyorova from Uzbekistan, and Elnur Mammadli from Azerbaijan, alongside long-time world-level contenders including Abiba Abuzhakynova, point to the region’s sustained presence at the sport’s highest level—a pattern previously noted by The Times of Central Asia during its coverage of the Paris 2024 Olympic cycle.

That influence extends beyond the competitors themselves. Following the conclusion of the opening-day contests in Paris, Timur Kemell, a member of the official International Judo Federation (IJF) ceremony delegation of Kazakh origin, took part in presenting the medals. Kemell has been active in regional and international judo governance and development, participating in events organized under the auspices of the IJF.

[caption id="attachment_43588" align="aligncenter" width="812"] Day 1 Medal Ceremony: Timur Kemell, Dilshot Khalmatov, Balabay Aghayev, Izhak Ashpiz, Aman Bakhytzhan, and David Inquel at the Paris Judo Grand Slam; image: International Judo Federation (IJF)[/caption]

The Paris Judo Grand Slam was officially opened by the International Judo Federation, with Marius Vizer, President of the IJF, and Stéphane Nomis, IJF Vice President and President of the French Judo Federation, leading the ceremony. Award presentations throughout the event also featured figures from sport and culture, including David Inquel, Albano Carrisi, Corinne Virulo-Cucchiara, Igor Tulchinsky, and Erika Merion, underscoring the tournament’s institutional and international stature.

At the Paris Judo Grand Slam, Eurasia’s role was not defined by flag dominance or overall medal totals, but by something more enduring: a deeply rooted martial-arts culture that continues to shape the technical and competitive foundations of international judo on one of the sport’s most visible global stages.

Day 1 Medal Ceremony: Timur Kemell, Dilshot Khalmatov, Balabay Aghayev, Izhak Ashpiz, Aman Bakhytzhan, and David Inquel at the Paris Judo Grand Slam; image: International Judo Federation (IJF)[/caption]

The Paris Judo Grand Slam was officially opened by the International Judo Federation, with Marius Vizer, President of the IJF, and Stéphane Nomis, IJF Vice President and President of the French Judo Federation, leading the ceremony. Award presentations throughout the event also featured figures from sport and culture, including David Inquel, Albano Carrisi, Corinne Virulo-Cucchiara, Igor Tulchinsky, and Erika Merion, underscoring the tournament’s institutional and international stature.

At the Paris Judo Grand Slam, Eurasia’s role was not defined by flag dominance or overall medal totals, but by something more enduring: a deeply rooted martial-arts culture that continues to shape the technical and competitive foundations of international judo on one of the sport’s most visible global stages.

Abdukodir Khusanov Named Manchester City’s Player of the Month for January

Uzbekistan national team defender Abdukodir Khusanov has been named Manchester City’s Player of the Month for January, marking a major milestone in his early Premier League career. The club announced that Khusanov won the fan vote by a wide margin following a string of standout performances. The 21-year-old made seven appearances during the month, demonstrating consistency and adaptability while partnering with various defenders. Manchester City praised Khusanov’s composure and tactical discipline, noting that his decision-making under pressure set him apart. He finished ahead of high-profile teammates, including goalkeeper Gianluigi Donnarumma and club captain Bernardo Silva, to earn his first individual accolade at the club. Khusanov’s rise at City has drawn significant attention in Uzbekistan, where he is regarded as one of the country’s brightest footballing talents. His January performances reinforced that status, as he secured a regular spot in the defensive lineup and proved dependable in critical matches. Ahead of a UEFA Champions League fixture in January, Manchester City head coach Pep Guardiola commended the young defender’s rapid development. “Just read the media, how they praised Khusanov. They’re right. He’s top,” Guardiola said, describing the player’s recent form as “exceptional.” Khusanov played the full 90 minutes in City’s Champions League clash against Norway’s Bodo/Glimt on January 20, anchoring the defense despite the team’s defeat. Guardiola also highlighted Khusanov’s discipline during earlier periods of limited playing time, citing his professionalism and commitment to improvement as a reflection of his football education in Uzbekistan.

Uzbekistan, Pakistan Set $2 Billion Trade Target Following High-Level Talks in Islamabad

Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev arrived in Islamabad on a state visit on February 5, marking a new chapter in Uzbekistan-Pakistan relations. According to official sources, the Uzbek leader’s aircraft was escorted by Pakistan Air Force fighter jets upon entering the country’s airspace. At Nur Khan Airbase, Mirziyoyev was received by President Asif Ali Zardari, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, and senior Pakistani officials. Shortly after his arrival, Mirziyoyev visited the headquarters of Global Industrial & Defence Solutions, where he met with Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff, Field Marshal Asim Munir. The two sides discussed strengthening the strategic partnership, with an emphasis on military and military-technical cooperation. Areas of focus included deepening collaboration between defense industry enterprises, expanding training for military personnel, sharing operational experience, and organizing joint exercises. Both countries agreed to draft a roadmap for future defense cooperation. Later that day, Mirziyoyev held one-on-one talks with Prime Minister Sharif and chaired the inaugural meeting of the High-Level Strategic Cooperation Council. At the meeting’s outset, the Uzbek president extended greetings in advance of the holy month of Ramadan and Pakistan Day. Discussions centered on implementing existing agreements and expanding cooperation across political, economic, and humanitarian spheres. Trade and economic cooperation featured prominently. Bilateral trade reached nearly $500 million by the end of last year, and approximately 230 Pakistani-capital companies are currently operating in Uzbekistan. Air connectivity and banking ties between the two countries are also expanding. Ongoing joint ventures span textiles, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, agriculture, and other sectors. An exhibition of Uzbek industrial products is being held in Islamabad as part of the visit. The two leaders agreed to set a goal of raising bilateral trade turnover to $2 billion in the near future. Key measures include expanding the list of goods under the Preferential Trade Agreement, easing phytosanitary requirements for Uzbek agricultural exports, and increasing the use of Uzbekistan’s trade houses in Lahore and Karachi. A joint project portfolio valued at nearly $3.5 billion has already been developed. Transport and logistics were another central topic. Both sides emphasized the strategic importance of advancing the Trans-Afghan railway and supporting the Pakistan-China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan transport corridor. They also agreed to establish an Uzbek-Pakistani Forum of Regions, with the inaugural meeting scheduled to take place this year in Uzbekistan’s Khorezm region. Cultural cooperation was also addressed. Plans include hosting Uzbekistan Culture Weeks and Uzbek Cinema Days in Pakistan and exploring the creation of a joint cultural center in Lahore dedicated to the Baburid heritage. The visit concluded with the signing of a Joint Declaration and a series of agreements spanning diplomacy, trade, defense, transport, agriculture, digital technologies, culture, security, and regional cooperation. Mirziyoyev also extended an invitation to Prime Minister Sharif for a return visit to Uzbekistan.

Breaking into Project Vault: A U.S. Role for Central Asia’s Strategic Minerals

The Trump Administration has decided to go head-to-head with Beijing to secure an independent supply chain for critical minerals and insulate U.S. industries from supply shocks. Among many initiatives, the United States launched Project Vault on February 2 to establish a U.S. Strategic Critical Minerals Reserve. The public-private stockpile is expected to secure essential minerals and metals for U.S. national security purposes and high-technology industries. The effort formalizes the U.S. strategy to diversify critical mineral supply chains away from rival China and, in the process, harness broader global capacity. As part of this effort, mineral-rich Central Asia is already factoring heavily in U.S. foreign and economic policy thinking. Participating in the front row of the 2026 Critical Minerals Summit, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan were invited to engage in Washington’s global effort to build resilient global supply chains. But Project Vault is a critical and separate component of the administration’s focus. Formally approved by the Export-Import Bank of the United States (EXIM) on February 2, Project Vault will be backed with up to $10 billion in long-term financing and an additional $2 billion in private sector participation. In sites across the country, the initiative will establish stores of critical minerals and rare earth elements essential for aerospace, defense, semiconductors, advanced manufacturing, renewables, and electric vehicles. The stockpile’s structure will be operated as a public-private partnership that enables manufacturers, trading firms, and private capital providers to jointly participate. Rare earths, copper, lithium, titanium, scandium, gallium, and germanium are all key minerals highlighted by the U.S. Department of the Interior that underpin modern technologies and demonstrate U.S. vulnerability to supply chain disruptions. Why a Strategic Mineral Reserve? The initiative is a direct response to perceived risks posed by China’s relative control of global critical mineral supply chains and markets, as well as Beijing’s use of trade restrictions, protectionism, and the weaponization of access to certain critical minerals. China controls a commanding share of the mining, refining, and processing of rare earths and related materials. Due to years of strategic planning and investment, Beijing has leveraged state subsidies and pricing controls to develop and secure between 80%-100% of rare earth processing capacities that have dominated international markets and disincentivized competitors for decades. Past export controls and export-license restrictions imposed by Beijing have underscored how critical mineral supply can become a tool of geopolitical leverage. China has at times restricted rare earth exports to Japan, Sweden and the United States in what is defined by many as supply-chain protectionism. Such actions can disrupt U.S. production for industries that rely on stable supplies to manufacture semiconductors, defense systems, and clean energy technologies. Project Vault is, therefore, conceived not merely as a reserve but as a mechanism to stabilize U.S. markets, to reduce reliance on China, and to signal a long-term commitment to diversified supply chains. Much like the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve acts to cushion energy price shocks, the mineral reserve is expected to serve as a similar buffer. Operational and Financial Dimensions Project Vault’s financing model expects a return on investment, as private firms will be paying for access and storage, with mining partners benefiting from stable demand. EXIM’s role and risk will come from using government financing to stopgap and underwrite long-term mineral extraction and processing ventures that private capital was unwilling or under-resourced to develop. However, stockpiling raw materials is not a panacea. Project Vault cannot substitute for the lack of downstream processing and refining, which are still largely concentrated in China. Any true U.S. reorientation will require not just investments in mining, but also in value-additive refining and processing capacities, which are not part of the stockpile initiative. Central Asia’s Strategic Mineral Potential While Project Vault focuses first on securing strategic mineral flow and shielding domestic access from global shocks, its ultimate success will depend on a significant diversification of upstream supply. This is where Central Asia can play a key role. Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan sit atop significant deposits of a wide range of strategic minerals identified as critical by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). While the United States began surveying and inventorying the region’s rare earth deposits in 2012, Central Asia didn’t draw significant attention until recently. Despite Kazakhstan being the world’s largest supplier of uranium since 2009, holding up to half of the world’s supply of tungsten, and Tajikistan producing approximately a quarter of global antimony supply, U.S. supply chains have found the region too remote. However, as Washington has sought greater independence from sole-sourced materials from China, the rare earth and strategic metal deposits found across the region are now seen to represent a significant alternative for U.S. policymakers. Collectively, Central Asia has deposits of over 25 different minerals that the United States designated as critical. The region is also rich in manganese, chromium, lead, zinc, and titanium reserves that further underscore the region’s strategic value to U.S. industrial and manufacturing interests. Though much of Central Asia’s mineral wealth remains underdeveloped or primarily exported as raw materials to China and Russia, change has appeared on the horizon. Washington’s recent cascade of high-level engagements that involve Central Asia at multiple levels, including an invitation for Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to attend the 2026 G20 summit, indicates a broader commitment and continued interest in developing strong, long-term partnerships with the region that include but are not limited to extractive mineral development. From C5+1 to B5+1 Over the past year, the Trump administration has signaled a clear evolution in how it sees Central Asia. Moving deliberately from high-level diplomatic engagement toward more commercially anchored strategies, Washington is working to translate political interest into economic results. This shift is evident in the augmentation of the long-standing C5+1 diplomatic framework to include a series of visits of Presidential envoys focusing on economic engagement and the continued commitment to the B5+1 business platform. The transition reflects a White House belief that Central Asia’s strategic potential cannot be realized through diplomacy alone. The C5+1, launched in 2015, has served as a principal vehicle for U.S. engagement with the five Central Asian countries. Initially conceived as a consultative forum, it expanded over time as a State Department-led effort to encompass regional security, economic development and reform, energy cooperation, and connectivity. In November 2025, the framework reached a new level of political significance with the first-ever White House summit for C5 leaders. That meeting underscored a continuing and deepening U.S. commitment to the region, with senior leadership engaging bilaterally and regionally on a wide range of issues and shared strategic concerns. Critical minerals featured prominently in those discussions, as U.S. officials emphasized their own need to diversify global mineral supply chains and reduce dependence on China. Central Asian leaders highlighted the substantial potential of their mining sectors and a corresponding desire to expand economic partnerships beyond traditional ties to China and Russia. The 2024 C5+1 Critical Minerals Dialogue, while once a relevant channel to highlight greater cooperation in the mining sector, has since been significantly supplemented. Breaking with Diplomatic Tradition In its desire to speedily ramp up critical mineral procurements, the Trump White House saw too many limits in traditional diplomacy for working with Central Asia. That perspective has driven greater emphasis in the use of Presidential envoys, high-level deal-making events, and the B5+1 mechanism to foster business-focused initiatives designed to create greater ties between U.S. private capital and commercial actors in the region. Organized with support from the Center for International Private Enterprise, the B5+1 is an example of the broader U.S. strategy to mobilize the private sector as a primary engine of economic engagement. The 2026 B5+1 Forum in Bishkek builds on the inaugural 2024 Almaty meeting and illustrates the thinking behind the Trump administration’s shift. The forum agenda focuses on sectors where strategic interests and commercial opportunities overlap, such as critical minerals, transport and logistics, finance, and technology. By convening U.S. firms, Central Asian companies, and government officials in a single forum, the B5+1 aims to move beyond policy statements toward concrete investment pathways, addressing barriers such as financing gaps, regulatory uncertainty, and infrastructure constraints. As part of this massive effort, the White House is also catalyzing the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), the United States Trade and Development Agency, and EXIM Bank to promote U.S. critical mineral supply chain security through development and finance efforts aimed at reducing China’s stranglehold on critical minerals. Each agency is expanding its work in Central Asia, bringing financial and technical resources to projects that speed up cooperation in this key terrestrial sector. Taken together, the transition from a standalone C5+1 to include a broader platform of concentrated business investment and engagement reflects an administration increasingly focused on operationalizing an implicitly proactive Central Asia strategy. While diplomatic lifting has created a solid foundation to signal political commitment and strategic intent, business-driven cooperation is now Washington’s focus and metric for delivering results. In the context of initiatives like Project Vault, this evolution suggests that Washington now sees Central Asia not just as a geopolitical partner, but as a potential long-term contributor to diversified, market-based supply chains capable of supporting U.S. economic and national security objectives. From Strategy to Structure Beyond the Critical Minerals Summit, the launch of Project Vault in 2026 represents a decisive policy shift toward treating U.S. critical mineral supply as an imperative of economic and national security. In doing so, the United States is opening a new chapter in supply-chain diplomacy that recognizes geopolitical risk, technological competition, and the strategic value of diversified resources. Central Asia’s expansive and underdeveloped mineral wealth positions the region well to become a key partner in this endeavor. Through a panoply of engagement mechanisms, the United States is seeking not only to counterbalance China’s strategic mineral processing and export monopolies but to build resilient collaborations with Central Asia that create interconnected and interdependent, multinational supply chains. This emerging partnership carries promise for powering future economies, but requires sustained investments, mutually beneficial agreements, and long-term commitments to counter the inevitable shifts in geopolitical currents. If successful, U.S.-Central Asian partnerships could significantly alter the composition of global critical mineral markets by contributing to a more diversified and resilient supply system. Nevertheless, the seeds of cooperation and inter-reliance between the United States and the Central Asian region augur a significantly higher level of trust, partnership, and shared strategic interests.

Sunkar Podcast

Central Asia and the Troubled Southern Route